NodeJS

Today we get an introduction to server-side JavaScript, including creating a Node project, using npm to install 3rd-party dependencies, and creating scripts in the package.json file.

Table of Contents

JavaScript on the Server (or anywhere)

Today we're learning about NodeJS. Node is a runtime environment written in JavaScript. You can think of a runtime environment as a virtual machine that can execute programs - kind of a very lightweight operating system.

Node is essentially the de facto dev environment for modern development. Want to use a framework like React, Vue or Svelte? Node is mandatory. Want to write unit tests? Node. Want to use compiled code like Typescript, SASS or Babel? Node, node, node.

Node can do a lot of different stuff, but we'll be learning how to use it the way most of you will end up using it most of the time: as a dev environment.

How to install NodeJS

First thing's first - check to see if you've already got node installed.

Open your terminal, and run this command:

node -vIf your terminal tells you what version of Node you've got installed, that means Node is installed!

If you get an error, follow the official instructions to download the Node installer for your operating system Opens in a new window.

Creating your first Node project

In your terminal, create a folder for your new project with this command:

mkdir my-node-projectNow change your location into that folder:

cd my-node-projectStart your new project with this command:

npm initThis prompt you for some inputs, but it's fine just to accept the defaults and/or leave things blank for now! Just keep hitting enter until it asks you Is this Ok?, and hit enter again.

Create a JavaScript file called index.js:

touch index.jsAt this point, you can open your project folder in your code editor. You should see two files: an empty index.js file, and a file called package.json, which is a JSON representation of the inputs you just gave through the command line. We'll talk more about the package.json more later, but for now, add the following to your index.js file:

console.log("Hello there.");Now in your console, run the following command:

node index.jsThis executes the JavaScript code in Node - and outputs to the terminal.

This can be a bit of a weird idea: JavaScript without a browser?? Console output outside the browser console? But it gets weirder - you can use JavaScript to access the file system, read & write files, create a web server, perform server-side encryption, and all kinds of other things.

Next, add the following line to the main object inside your package.json file:

"type": "module",This enables our use of our import/export statements that we used to work with modules. Modules are very important in Node!

What your package.json file should look like at this point

{

"name": "my-new-project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"type": "module",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC"

}Create a new file in your project called read-stuff.js

Add this code to your file:

import { readFileSync } from 'fs';

const fileData = readFileSync('index.js', 'utf8');

console.log(fileData);After you save your file, run the following command in the terminal:

node read-stuffThere's a couple things going on here:

- We imported a method from a NodeJS "native" module called "fs" (which stands for "file system"). Node has a lot of these built-in modules Opens in a new window, each of which has a ton of methods we can use.

- The method we imported is called "readFileSync", which, as you may have guessed, synchronously reads a file. (Note: a lot of Node is asynchronous by default - if you find yourself getting into trouble with the async functions, there's usually a synchronous alternative).

- "readFileSync" returns the data it reads from the file.

If you're reading older tutorials that work with Node, you'll likely see this older require() syntax for importing modules:

const { readFileSync } = require('fs');

const fileData = readFileSync('index.js', 'utf8');

console.log(fileData);This known as 'CommonJS' syntax. CommonJS is a specification project started by Mozilla engineer Kevin Dangoor back in 2009, which introduced the idea of modules in JavaScript.

The CommonJS syntax above accomplishes the same thing as our import syntax, and it's pretty easy to translate one to the other if you're reading documentation or tutorials that are using the syntax that you're not using. To see how they compare, have a look at the code above, and compare it to the code we put into our read-stuff.js file.

The one thing to note is, to use the require() syntax, you have to remove this line from your package.json file:

"type": "module",... meaning you can't use the import syntax anymore. You have to either use import or require(); you can't use both.

I've been showing you the `import/export` syntax, because it's part of vanilla JavaScript at this point, and all Node's documentation is written using this syntax at this point. CommonJS is likely on its way out.

- Introduction to CommonJS Opens in a new window, Flavio Copes 2018

Node Packages

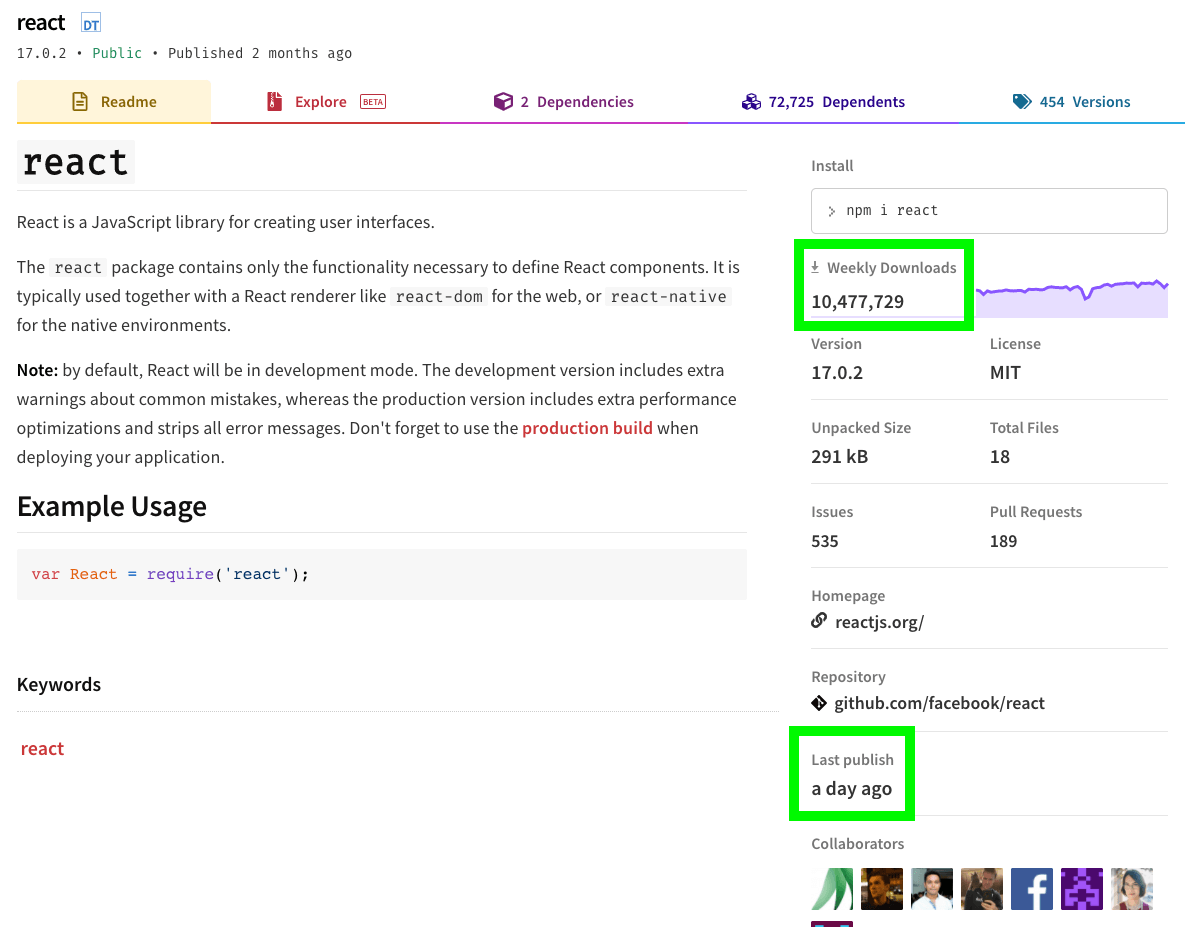

One of the major reasons that Node is the go-to dev environment these days is because of the absolutely massive ecosystem of Node packages.

What is a package?

In Node, a package is any file or folder that is described by a package.json file (like the one we created today).

In our line of work, when we say 'package', what we're typically referring to is a Node module (the kind of file that exports values and functions that you can import into the JS file you're working on) that has been made publicly available.

In the same way we used to download, say, jQuery and load it on our web pages, we now download dozens of modules (along with the potentially hundreds of modules that those modules themselves depend on), and use them primarily (but not exclusively) to help us create our web applications, and occasionally to include in the end-result.

You've heard of React & Vue? To start a React or Vue project, the first thing you do is install them as Node packages. Remember two weeks ago when we talked about Webpack, or the various other bundlers? Yep, all Node packages. Sass, Babel, Eslint? Node packages. jQuery? Yup, now that's a Node package, too.

Why is all this stuff free??

The business model of open-source software is a whole other topic, but I happen to think it's super-cool that we get all these packages without having to pay.

You should really consider contributing to open-source software. It's pretty simple - when you like something but you see some way it could be improved, go to the github repo for that package, clone it, make the change, and submit a pull request. That, or publish your own package to npm (it's really easy - instructions are in the "further reading" for this section).

Not only is it being a good citizen, it's also a great way to add stuff to your resumé.

Now, if each one of these packages was something that we had to download from its own website, make a folder for, keep up-to-date, reference its file path in our includes, etc. etc., that would be a nightmare!

Luckily, when you install Node, it comes with a piece of software called a package manager.

npm

npm is Node's package manager. It lets you easily install packages from the npm registry Opens in a new window.

All you have to do to install a package (and all its dependencies) in your project is run the following command:

npm install [whatever the package name is]To get rid of the package, all you have to do is

npm uninstall [whatever the package name is]Is this safe??

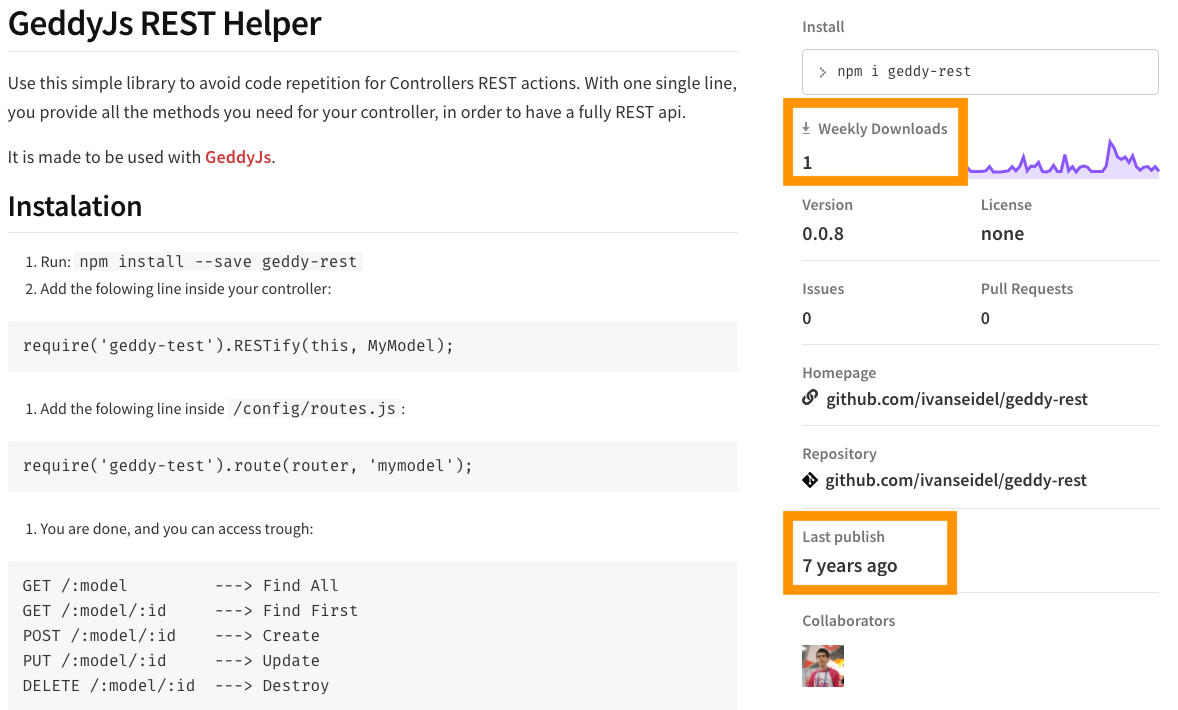

You're downloading and running someone else's code. So no, it's not perfectly safe. There are some things we can do to make it safer, though.

First off, understand that it is open-source code, meaning that it's code anyone can see. This adds a level of trust-worthiness to packages, especially ones that are popular and actively maintained.

npm also maintains an active directory of security advisories Opens in a new window. However, you don't have to search the directory every time you install a package. npm automatically checks packages (including their dependencies) for security vulnerabilities when you install them. You can also run this command any time you like with this command:

npm auditIt's not uncommon to see warnings about "deprecated" dependencies when you install packages - read through the advisories when you see them and take them with a grain of salt. It's rarely something malicious, most often just relying on other code that is out-of-date. The best security practice is to distinguish between code that is used to create your application, and code that will be included in the final product.

npm install vs. npm install --save-dev

When you install the Babel package in your project, its role is to transform your JavaScript into an older syntax, meaning you can write newer JavaScript, then transform it with Babel, then send your JavaScript to the user in a form that works in older browsers. What you're not doing is sending Babel to your users - they just get a regular JavaScript file. Babel is what we call a "dev dependency", which means you need it, but the end-user does not.

When you install React, you will end up sending code from the React package to your users. React is a "production dependency".

When you install a package, it's a good idea to make it clear whether it's going to be used just for the development process, or whether it'll be something included in the final product. This distinction is made in the command you use to install a package.

When you install a package, by default it's considered a production dependency. If you add --save-dev after the command install, it'll be remembered as a development dependency.

For example, the Mocha testing library is used for unit tests, which are not a part of the application when it's sent to the user's browser, so Mocha's documentation Opens in a new window tells us to install it like this:

npm install --save-dev mochaThis is important, because our deployment processes need to be able to build the application to deliver it to the user, and we wouldn't want to put a bunch of unnecessary packages in our deployment pipeline.

You know how I just said that your application "remembers" information about your dependencies? The way it remembers stuff is by writing it in simple JSON in a file called "package.json".

- Creating Node.js modules Opens in a new window (and publishing them to npm, as a publicly available package), npm Docs

Anatomy of a package.json File

Remember at the beginning, when we created a Node project, and ran the command npm init?

That command generated a file called "package.json". A package.json file stores information about your Node project, sorta like how a <head></head> element stores information about your HTML document.

Mostly it's basic information like the project's title, description and author. There's two things in there, though, that I think merit a little explanation: dependencies and scripts.

"dependencies" and "devDependencies"

These objects contain records of the packages that have been installed with npm install. Don't edit this part of the package.json file directly.

Install packages with the npm install [whatever the package name is] command.

Uninstall packages with the npm uninstall [whatever the package name is]

Note: You can install or uninstall multiple packages with the same command: just add the names of all the packages to your command like this:

npm install --save-dev [package-1] [package-2] [package-3] If you install a package without the --save-dev flag, the package will be listed under "dependencies". If you install a package by running the command npm install --save-dev [whatever the package name is], it will be listed under "devDependencies".

Did you forget to use ‐‐save‐dev? That's okay! Just run npm install again, this time with ‐‐save‐dev, and your package will get moved from dependencies to devDependencies in package.json.

When this is really handy

One reason this comes in really handy: when you download or git clone a project, and it already has a package.json file, you can just run this command:

npm installYou don't have to specify any package names, or specify --save-dev - npm will automatically download and install all packages that are listed under "dependencies" and "devDependencies".

This is what allows us to .gitignore our whole node_modules folder.

Wait, what's the node_modules folder?

The node_modules folder is where all your modules get saved when you install them with npm install.

Let's go back to our my-node-project and look at how this works.

In your terminal, run these commands:

npm install chart.jsnpm install ‐‐save‐dev mochaThis is going to install a popular front-end javascript library for creating charts and graphs called chart.js, and a popular unit testing library called 'mocha'.

(We use npm install for chart.js because it's a JavaScript library that will be included in our pages when they run in the users' browser. We use npm install ‐‐save‐dev for mocha, because it will be used by developers for running unit tests, but will not end up in the finished product.)

Wait, I thought you said we could install multiple packages with a single command?

Yep, but only if they're the same type of dependency - either production or development. If you want to install some packages as dev dependencies, and some as production dependencies, you have to install them with separate commands.

That being said, you can concatenate commands with a double ampersand, and they'll be run one after the other. If you wanted to run both of the above commands with a single press of your enter key, you could write them like this:

npm install chart.js && npm install ‐‐save‐dev mochaWhat your package.json file should look like at this point

{

"name": "my-new-project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"type": "module",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"chart.js": "^3.3.2"

},

"devDependencies": {

"mocha": "^8.4.0"

}

}After you run those commands, a folder called 'node_modules' is created in your project. If you open it up, it's got about 83 folders in it, including one called 'chart.js' and one called 'mocha'.

What the heck are those other folders? Well, just like your project depends on 'mocha' for running unit tests, and 'chart.js' for creating charts in the browser, 'mocha' and 'chart.js' depend on other packages. The other folders in 'node_modules' are other packages that your installed packages depend on. Are JavaScript modules fun?

Thanks to our package.json file, you could delete the whole node_modules folder anytime you like, and run the command npm install, and it will automatically create the node_modules folder and download all your dependencies again.

The size of the dependencies, along with the ease with which we can install them, means the you should basically always add the 'node_modules' folder to you .gitignore file - no sense in clogging up our repo with someone else's code when we don't need to.

What's really cool about node_modules & npm

The node_modules folder is big and complicated. The good news is you rarely have to go in there.

Node makes it really easy to reference the packages we install when we want to use them.

In the package.json file for my-new-project, replace the "test" script with the following:

"test": "mocha test/my.test.js",Make sure you have the mocha testing library installed globally by running this command:

npm install --global mochaThen install mocha, and the "assertion library" package 'chai' in your project by running this command:

npm install ‐‐save‐dev mocha chaiDon't know what a testing library or an assertion library is? That's okay! We're going to learn all about this stuff next week!

Also, if you've already installed mocha, that's okay! npm checks to see if something's already installed, so there's no harm in running the command twice.

In my-new-project, create a folder called 'test', and inside that folder, create a file called 'my.test.js'.

Want to accomplish this all from the command line?

mkdir test && touch test/my.test.jsInside my.test.js, paste the following code:

import { expect } from 'chai';

const foo = 'bar';

it('should be a string', function() {

expect(foo).to.be.a('string');

});Now, in your console, you can run the command npm run test.

Congratulations! You've run your first unit test!

What I really want you to notice, though, is the import statement we used. We didn't have to reference a specific JavaScript file. We just had to put from '[package name]';, and Node figured everything out for us!

"scripts"

The other object in package.json I wanted to tell you about is the "scripts" object.

In scripts, you can create commands that get called with npm. If you create a named script inside the "scripts" object, you can run commands (including packages you've installed) simply by running this command in your console:

npm run [script-name]In package.json, in the "scripts" object, add "shell-script": "ls", then run the following command in your console:

npm run shell-scriptThis runs the command "ls" in your shell, and lists the files and folders in the root of your project. Now, obviously, it's shorter just to write "ls" than it is to write "npm run shell-script", but as soon as things start getting to be, you know, stuff that you'd want a shortcut for, then the script object comes in real handy.

"build": "if [ ! -d public/js ]; then mkdir -p public/js; fi; cp node_modules/chart.js/dist/chart.min.js public/js"The best reason to create these scripts is to group together commands into easy-to-remember aliases that map onto the steps in your development process, like this:

"test": "mocha test/my.test.js && eslint src/my-script.js",

"build": "webpack",

"production": "npm run test && npm run build"

The World's Simplest Static Site Generator

I've created a little exercise so you can figure out what you've understood today, and what you should ask me questions about.

- Clone this repo: Simple Static Site Generator Opens in a new window

- Use

npm installto install the necessary dependencies - Read through the README.md and package.json files to understand what the application does

- Use the scripts from package.json to create a new page and see it in your browser