Today we look at the OWASP Top 10 Web Application Security Risks.

Who is OWASP

OWASP, or the "Open Web Application Security Project", is a non-profit community with >10,000 volunteers dedicated to finding, documenting, and providing solutions to web security issues.

You should totally check out a meeting of the Toronto chapter Opens in a new window.

Since 2003, they've been publishing their "Top 10 Web Application Security Risks". Today's lesson is based on familiarizing yourself with the current top ten (as of 2021) so that you can keep your users safer.

Next week, we'll be talking about where you're most likely to find these problems, and how to prevent or solve them. Today we're just looking at the types of vulnerabilities that can pop up in different places in your application.

None of these security risks are particular to a specific language or any other point-of-entry. These are concepts that will pop up in different ways in different situations.

If we were talking about home security instead of web security, these security risks would be a lock-picking set - tools for malicious actors ("bad guys") that can be adapted to different situations.

If we were talking about home security instead of web security, these security risks would be a lock-picking set - tools for malicious actors ("bad guys") that can be adapted to different situations.

The Top Ten

Injection

Injection flaws, such as SQL, NoSQL, OS, and LDAP injection, occur when untrusted data is sent to an interpreter as part of a command or query. The attacker’s hostile data can trick the interpreter into executing unintended commands or accessing data without proper authorization.

We use our backend code to interact with a data source.

$query = "SELECT * FROM articles";Injection becomes an issue when we use data that the user can edit - for example, if we were to take data from a form and insert it directly into the database, or if we were to use query parameters from the URL in a SELECT statement:

// mysite.com/index.php?article=1234

$articleId = $_GET['article'];

// Gets '1234'

$query = "SELECT * FROM articles

WHERE articleId = $articleId";

// Database runs `SELECT * FROM articles

// WHERE articleId = 1234`Since the url is something a user can edit, some user could alter the URL to something like this:

// mysite.com/index.php?article=1234;DELETE FROM articles

$articleId = $_GET['article'];

// Gets '1234;DELETE FROM articles'

$query = "SELECT * FROM articles

WHERE articleId = $articleId";

// Database runs `SELECT * FROM articles

// WHERE articleId = 1234;DELETE FROM articles`Now, this is a bit of a silly example, but the point stands - the php and database server are just going to shrug and run the code you're providing. Like a dumb news anchor from San Diego.

The solution for this is to make sure that nothing provided by public users can be executed as code. We'll look at techniques for this next week.

Broken Authentication

Application functions related to authentication and session management are often implemented incorrectly, allowing attackers to compromise passwords, keys, or session tokens, or to exploit other implementation flaws to assume other users’ identities temporarily or permanently.

Broken authentication could mean a great number of things. Here are some of the examples OWASP provides:

- Not protecting against brute force attacks

- Allowing users to use default, weak, or well-known passwords, such as "Password1" or "admin/admin"

- Using weak or ineffective username/password recovery and forgot-password processes, such as “knowledge-based answers”

- Doesn't use multi-factor authentication

- Doesn't properly log a user out when they log out or are inactive for a long period

Sensitive Data Exposure

Many web applications and APIs do not properly protect sensitive data, such as financial, healthcare, and PII. Attackers may steal or modify such weakly protected data to conduct credit card fraud, identity theft, or other crimes. Sensitive data may be compromised without extra protection, such as encryption at rest or in transit, and requires special precautions when exchanged with the browser.

This one's a simple idea - any unencrypted sensitive data is a security risk, particularly when that data is moving from one place to another.

There are some easy solutions (mandatory HTTPS for everything, use up-to-date cryptography), but there are also some weak points that are technically challenging.

XML External Entities (XXE)

Many older or poorly configured XML processors evaluate external entity references within XML documents. External entities can be used to disclose internal files using the file URI handler, internal file shares, internal port scanning, remote code execution, and denial of service attacks.

Essentially, the application that processes an XML file can be exploited to do bad stuff (like read system files Opens in a new window, or detonate an XML Bomb Opens in a new window).

Some might argue that this is a type of "injection", but it's a type that's significant enough to get it's own entry in the top 10.

Broken Access Control

Restrictions on what authenticated users are allowed to do are often not properly enforced. Attackers can exploit these flaws to access unauthorized functionality and/or data, such as access other users’ accounts, view sensitive files, modify other users’ data, change access rights, etc.

This is a catchall for whenever a user can do something they're not supposed to be able to do. Ever edit the URL of a website and end up someplace that obviously isn't for public users? That's one type of Broken Access Control.

Security Misconfiguration

Security misconfiguration is the most commonly seen issue. This is commonly a result of insecure default configurations, incomplete or ad hoc configurations, open cloud storage, misconfigured HTTP headers, and verbose error messages containing sensitive information. Not only must all operating systems, frameworks, libraries, and applications be securely configured, but they must be patched/upgraded in a timely fashion.

This is another catchall for any part of the application that's not set up properly (we're going to spend a lot of time on HTTP headers next week), or is out-of-date. Time to turn on those automatic updates in your Wordpress site!

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

XSS flaws occur whenever an application includes untrusted data in a new web page without proper validation or escaping, or updates an existing web page with user-supplied data using a browser API that can create HTML or JavaScript. XSS allows attackers to execute scripts in the victim’s browser which can hijack user sessions, deface web sites, or redirect the user to malicious sites.

OWASP identifies three types of XSS:

- Reflected XSS

Please click on this link: <a href='http://example.com/index.php?user=<script>window.onload = function() {var AllLinks=document.getElementsByTagName("a");AllLinks[0].href = "http://badexample.com/malicious.exe";}</script>'>example.com</a> - Stored XSS The bigger, meaner brother of the above is when a user can use a similar technique to submit data to a website containing a malicious script (injection), which then gets executed when other users visit the site. The previous example relies on social engineering (encouraging someone to click your sketchy link), whereas Stored XSS is dangerous for a much wider audience.

- DOM XSS Similar to the above, except taking advantage of client-side DOM rendering, like when a single-page application (React, for example), puts together the web page based on data the user can edit (the simplest example being URL parameters, as above). Not terribly different from either of the first two, describing this category serves to remind us that SPAs have added new ways for XSS to happen.

Please click on this link: <a href='http://example.com/index.php?user=<script>window.onload = function() {var AllLinks=document.getElementsByTagName("a");AllLinks[0].href = "http://badexample.com/malicious.exe";}</script>'>example.com</a>If someone clicked on this link and went to a site that was pulling the user's name directly from the query parameter, it could inject a script that would change the first link on the page into something nefarious!

The bigger, meaner brother of the above is when a user can use a similar technique to submit data to a website containing a malicious script (injection), which then gets executed when other users visit the site. The previous example relies on social engineering (encouraging someone to click your sketchy link), whereas Stored XSS is dangerous for a much wider audience.

Similar to the above, except taking advantage of client-side DOM rendering, like when a single-page application (React, for example), puts together the web page based on data the user can edit (the simplest example being URL parameters, as above). Not terribly different from either of the first two, describing this category serves to remind us that SPAs have added new ways for XSS to happen.

Insecure Deserialization

Insecure deserialization often leads to remote code execution. Even if deserialization flaws do not result in remote code execution, they can be used to perform attacks, including replay attacks, injection attacks, and privilege escalation attacks.

Okay, so - full disclosure, I do not have a computer science degree. One of the challenges of putting together the materials for the security portion of this course is that we talk about programming concepts that could apply to many different computer languages (that's kind of what CompSci is about). Sometimes I want to talk about this stuff by putting it into the context of a particular language, but that might not capture the whole concept. The alternative is using CompSci language that I'm not totally comfortable with. I'm just throwing that out there if we have any CompSci people in the class who know more than I do about something like deserialization. To those people, I apologize, and please let me know how I can make this better!

Okay, so let's first talk about serialization:

Serialization

Serialization is when you turn complex things (like objects or functions) into something simple, like a string.

let myFunc = function(a,b) {

return a + b;

}

console.log(myFunc(1,2)); // 3

// Serialize the function

myFunc = myFunc.toString();

console.log(myFunc(1,2));

// Uncaught TypeError: myFunc is not a function

console.log(myFunc)

// "function (a, b) {

// return a + b;

// }"Serialization is pretty common, as it lets us store code and other data efficiently in a database.

To retrieve that code from the database and then run it, we'd need to turn it back into a function (or object, or what have you). That process is called deserialization.

Deserialization

Deserialization is the process of turning "flat" data (think of it as plain text) into code that a computer can understand.

let json = '{"result":true, "count":42}';

console.log(json.count);

// undefined

// Deserialize JSON

json = JSON.parse(json);

console.log(json.count);

// 42If a malicious user can get nasty code into your serialized data, then it can get executed when the data is deserialized if that process is not secured.

Personally, I think deserialization attacks have the coolest names: Java Serial Killer Opens in a new window Friday the 13th JSON AttacksPDF - Opens in a new window

I'm also a fan of the method names in the Python de/serialization module Opens in a new window which allows you to "pickle" (serialize) and "unpickle" (deserialize) your data.

Using Components with Known Vulnerabilities

Components, such as libraries, frameworks, and other software modules, run with the same privileges as the application. If a vulnerable component is exploited, such an attack can facilitate serious data loss or server takeover. Applications and APIs using components with known vulnerabilities may undermine application defenses and enable various attacks and impacts.

11 years ago, back when jQuery was a big deal, a fella named Paul Irish (one of the people who brought us the Chrome DevTools) read jQuery Opens in a new window. All 7179 lines of it (as of jQuery v1.4).

I thought this was incredibly impressive - reading the code you're running on your website.

When I make a website, I'm certainly not reading all the code of all the libraries I use to compile it. So how do I know it's safe? How do I know there isn't a vulnerability in there, just waiting to get exploited? How much worse would it be if, instead of a website, I was running software on a device that's hard to patch, like medical equipment, or a tractor?

Even more than serving users malicious scripts, this is a particular point of vulnerability on your server, because we tend to let our libraries have the same permissions as our handwritten code on the machine where we do sensitive stuff, like processing credit card information.

Insufficient Logging & Monitoring

Insufficient logging and monitoring, coupled with missing or ineffective integration with incident response, allows attackers to further attack systems, maintain persistence, pivot to more systems, and tamper, extract, or destroy data. Most breach studies show time to detect a breach is over 200 days, typically detected by external parties rather than internal processes or monitoring.

This one's pretty easy to understand - it's just not paying attention and not keeping track. If you're not monitoring your website or keeping records of what your server is doing, it's going to be a force multiplier Opens in a new window for malicious code.

- 1. Table of Contents

- 2. Who is OWASP

- 3. OWASP, or the "Open Web Application Security Project", is a non-profit community with >10,000 volunteers dedicated to finding, documenting, and providing solutions to web security issues.

- 4. Next week, we'll be talking about where you're most likely to find these problems, and how to prevent or solve them. Today we're just looking at the types of vulnerabilities that can pop up in different places in your application.

- 5. If we were talking about home security instead of web security, these security risks would be a lock-picking set - tools for malicious actors ("bad guys") that can be adapted to different situations.

- 6. The Top Ten

- 7. Injection

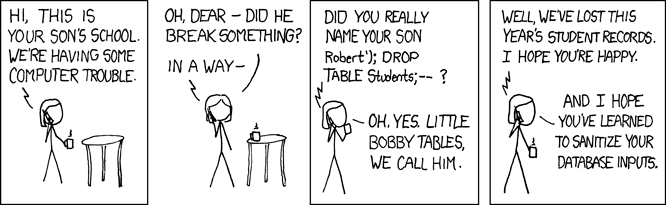

- 8. Her daughter is named Help I'm trapped in a driver's license factory. XKCD Opens in a new window

- 9. We use our backend code to interact with a data source.

- 10. Since the url is something a user can edit, some user could alter the URL to something like this:

- 11. Now, this is a bit of a silly example, but the point stands - the php and database server are just going to shrug and run the code you're providing. Like a dumb news anchor from San Diego.

- 12. Broken Authentication

- 13. Broken authentication could mean a great number of things. Here are some of the examples OWASP provides:

- 14. Sensitive Data Exposure

- 15. This one's a simple idea - any unencrypted sensitive data is a security risk, particularly when that data is moving from one place to another.

- 16. XML External Entities (XXE)

- 17. Essentially, the application that processes an XML file can be exploited to do bad stuff (like read system files Opens in a new window, or detonate an XML Bomb Opens in a new window).

- 18. Broken Access Control

- 19. This is a catchall for whenever a user can do something they're not supposed to be able to do. Ever edit the URL of a website and end up someplace that obviously isn't for public users? That's one type of Broken Access Control.

- 20. Security Misconfiguration

- 21. This is another catchall for any part of the application that's not set up properly (we're going to spend a lot of time on HTTP headers next week), or is out-of-date. Time to turn on those automatic updates in your Wordpress site!

- 22. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

- 23. OWASP identifies three types of XSS:

- 24. Reflected XSS

- 25. Stored XSS

- 26. DOM XSS

- 27. Insecure Deserialization

- 28. Okay, so - full disclosure, I do not have a computer science degree. One of the challenges of putting together the materials for the security portion of this course is that we talk about programming concepts that could apply to many different computer languages (that's kind of what CompSci is about). Sometimes I want to talk about this stuff by putting it into the context of a particular language, but that might not capture the whole concept. The alternative is using CompSci language that I'm not totally comfortable with. I'm just throwing that out there if we have any CompSci people in the class who know more than I do about something like deserialization. To those people, I apologize, and please let me know how I can make this better!

- 29. Serialization

- 30. let myFunc = function(a,b) { return a + b; } console.log(myFunc(1,2)); // 3 // Serialize the function myFunc = myFunc.toString(); console.log(myFunc(1,2)); // Uncaught TypeError: myFunc is not a function console.log(myFunc) // "function (a, b) { // return a + b; // }"

- 31. Serialization is pretty common, as it lets us store code and other data efficiently in a database.

- 32. Deserialization

- 33. let json = '{"result":true, "count":42}'; console.log(json.count); // undefined // Deserialize JSON json = JSON.parse(json); console.log(json.count); // 42

- 34. If a malicious user can get nasty code into your serialized data, then it can get executed when the data is deserialized if that process is not secured.

- 35. Personally, I think deserialization attacks have the coolest names: Java Serial Killer Opens in a new window Friday the 13th JSON AttacksPDF - Opens in a new windowI'm also a fan of the method names in the Python de/serialization module Opens in a new window which allows you to "pickle" (serialize) and "unpickle" (deserialize) your data.

- 36. Using Components with Known Vulnerabilities

- 37. 11 years ago, back when jQuery was a big deal, a fella named Paul Irish (one of the people who brought us the Chrome DevTools) read jQuery Opens in a new window. All 7179 lines of it (as of jQuery v1.4).

- 38. When I make a website, I'm certainly not reading all the code of all the libraries I use to compile it. So how do I know it's safe? How do I know there isn't a vulnerability in there, just waiting to get exploited? How much worse would it be if, instead of a website, I was running software on a device that's hard to patch, like medical equipment, or a tractor?

- 39. Insufficient Logging & Monitoring

- 40. This one's pretty easy to understand - it's just not paying attention and not keeping track. If you're not monitoring your website or keeping records of what your server is doing, it's going to be a force multiplier Opens in a new window for malicious code.

- 41. 10 / 10!